What it’s accomplished, what it hasn’t

Ahead of the release of preliminary Q1 2024 production and delivery figures, expected next week, it’s now official: Tesla has delivered more than 6 million vehicles since 2008, every one a battery-electric vehicle.

Its 5 million total last September got a lot of attention. But 6 million is more important, because it cements Tesla as the first company in all but 100 years to achieve a remarkable milestone.

Nearly 10 years ago, City Dwellers suggested Elon Musk had to deliver 6 million Teslas to become the highest-volume startup carmaker in the U.S. since the 1920s. That number today equates to what was done by the last U.S. startup to achieve significant volume production—more than 60 years ago. That would be Kaiser, a name now all but forgotten. Starting in 1945, Kaiser-Frazer (later Kaiser, then Kaiser-Jeep) built more than 700,000 cars.

Tesla Motors production line for Tesla Model S, Fremont, California

Here’s how we got to that 6 million: In 1950, U.S. vehicle sales of 8 million cars represented 80 percent of total global production of just under 10 million. The market today is nine times that size—almost 90 million vehicles a year, according to J.D. Power. U.S. sales for 2023, at 15.6 million in 2023, are at just 17 percent of that total, with China far and away the world’s largest car market. So Kaiser’s 700,000-plus (over 10 years) roughly scales up to Tesla’s 6 million (over 15 years).

With this latest milestone ticked off, it’s a good time to look at the things that Tesla has accomplished since 2008—and some of the things it hasn’t.

Produced our 6 millionth car!

Thank you to our owners & teams around the world for your support & hard work—it truly matters.

🌎🌍🌏❤️ pic.twitter.com/F4IeQtK0PS

— Tesla (@Tesla) March 29, 2024

What Tesla Has Done

The company has launched and built hundreds of thousands of its first two models (2012 Model S, 2015 Model X) and millions of its smaller, less expensive pair (2017 Model 3, 2020 Model Y). Its fifth model, the 2024 Cybertruck, is ramping up to what would widely be called mass-production levels. But beyond those products themselves, Tesla has logged other notable accomplishments that have transformed the world’s vehicle business.

2017 Tesla Model 3

Tesla kicked the global auto industry in the backside, hard

The emergence of Tesla as a volume carmaker in 2013 and 2014 profoundly rattled most of the world’s automakers, who had viewed the limited-production, expensive 2008-2011 Tesla Roadster as an interesting science experiment.

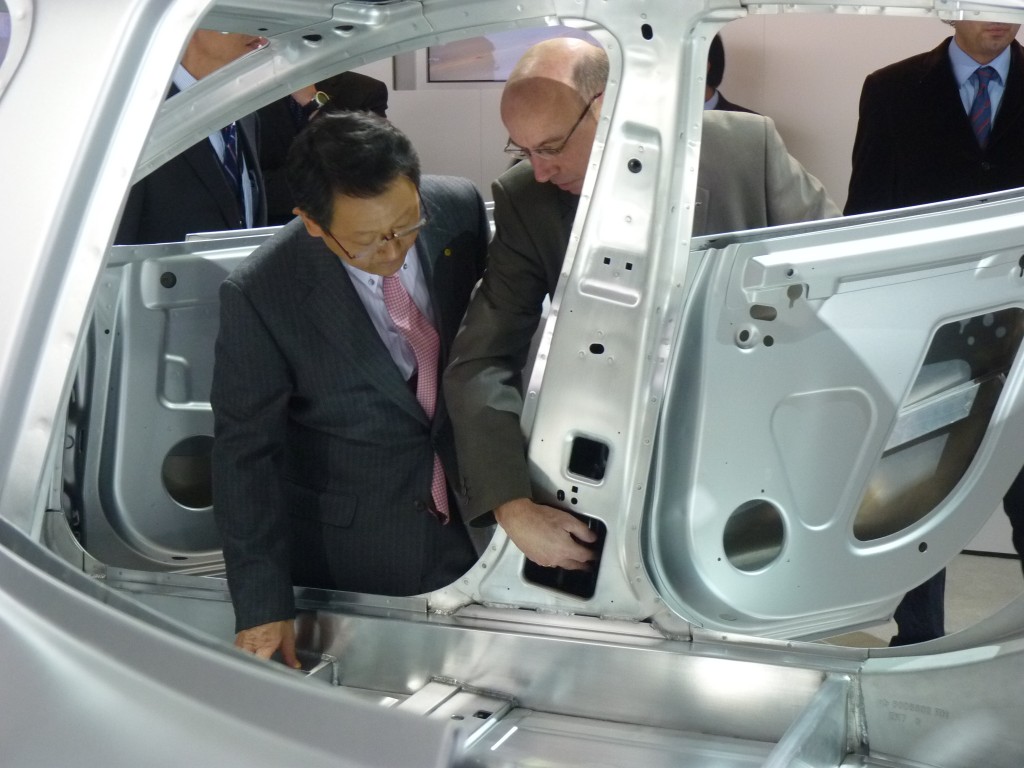

The nervousness started in 2011, when Tesla showed a stripped Model S body shell at that year’s Detroit auto show. It was impossible to photograph the shell given how many engineers and executives from other makers swarmed around it—including Toyota CEO Akio Toyoda.

Toyota Motor Corporation president Akio Toyoda, at Tesla stand, 2011 Detroit Auto Show

Ten years ago, a longtime insider in the German auto industry told us the story of what happened early in 2013, when one of the German prestige brands got its hands on a Model S. First, it took the Tesla to its test track and teardown facility, where the company’s test drivers hammered it around the track, recharged it, and hammered it again. Members of its product board were then told to come to the track and do the same. The Tesla was driven for several days at low speeds, high speeds, and everything in between; apparently it performed flawlessly.

Then the executives responsible for that maker’s future products convened a meeting. They concluded the Model S electric luxury sedan—a sexy all-aluminum vehicle from a carmaker that hadn’t existed 10 years before—provided a fast, comfortable, technologically advanced driving experience. No vehicle in their lineup, or even on the drawing board, could match the experience. That was deeply, profoundly unsettling to this particular maker of cars world-renowned for their brand image.

And that, kids, is how we came to have the Porsche Taycan.

Tesla Model S

Tesla showed EVs could be fast, sexy, and desirable

In the late 2000s, when Tesla was struggling to get the Roadster into production, one auto reporter dismissed EVs out of hand. “The only people who care about electric cars,” this person said, “are annoying environmentalists and smelly hippies. And they don’t buy new cars.” That attitude, along with the image of EVs as glorified golf carts (not helped by low-speed neighborhood electric vehicles from the likes of GEM), presumed that EVs could never be alluring vehicles in their own right.

That was wrong, as the now-classic design of the Model S showed 12 years ago. That design, its startling performance, and the smooth, calm driving experience likely got some people to buy a Tesla despite its electric powertrain. It was the most tech-forward car on the market, sure, but more important, it was sexy and it was cool.

Tour of Tesla battery gigafactory for invited owners, Reno, Nevada, July 2016

Tesla scaled up battery plants long before others

Tesla CEO Elon Musk first used the word “gigafactory” more than 10 years ago, in November 2013, as he discussed the company’s plans to scale up production to tens of thousands of cars a year, then hundreds of thousands. He had done the math and realized huge factories that built gigawatt-hours of battery cells every year would be needed for that many EVs. The first Gigafactory, outside Reno, Nevada, opened in July 2016, with the company’s cell partner Panasonic starting cell production in January 2017.

Even so, it took roughly five years for Panasonic to turn consistent profits from that site—indicating the difficulty of producing a new cell format, with a new chemistry, in a new building, using a new workforce that had never worked on batteries before. How hard is that? According to a battery engineer, it’s “really, really, really, really, really, really, REALLY hard.”

Tesla has to build several of these plants globally, ideally one per vehicle factory. The industry as a whole has to build many dozens of them—and as GM’s very slow ramp of its Ultium cells and vehicles suggest, our battery engineer wasn’t kidding. Tesla was far ahead of that curve.

Tesla Supercharger

Tesla Supercharger network at 25,000 U.S. connectors!

With ranges of more than 200 miles, every production Tesla easily surpassed the driving range of EVs from other makers, which spanned from 60 to 125 miles. But Tesla always intended its cars to be driven wherever any other car could go, including cross-country trips, so in 2012 it began construction of its first Supercharger DC fast-charging stations. Last September, it reached 50,000 Superchargers globally, of which roughly 21,000 of those were in the U.S.—and just six months later now, the Supercharger network stands at 25,000, according to the DOE.

Tesla’s Superchargers are reliable, easy to use (plug in, walk away), and benefit from the company having designed and built the hardware and software for both the charging stations and the cars that use them. It’s the model for a ubiquitous, reliable, seamless DC fast-charging network.

Other makers had no intention of spending the tens of billions of dollars to create such a network, and 10 years later, the result is a confusing collection of money-losing regional and national charging networks of questionable reliability.

As EV production scaled up, carmakers’ frustration with their charging “partners” reached a boiling point in 2022. Ford, which had been the most proactive, already resorting to its own “charge angels” to do the in-person spot-checking the charging networks omitted, shocked the industry last May. Its deal with Tesla to provide charging adapters and adopt the latest Tesla charging connector, now standardized, will give owners of its current EVs—and all the brands that have followed—the ability to charge at Superchargers. As of yet, with Ford and Rivian owners already tapping into Superchargers, it’s working.

2024 Tesla Model Y. – Courtesy of Tesla, Inc.

Tesla has sold more EVs than any other maker in the world

The idea that a scrappy startup could sell more battery-electric cars than the world’s biggest makers was laughable to those makers’ executives—until Tesla simply did it. It took the company from July 2012 to March 2020 to build its first 1 million vehicles. Then it added a factory in Shanghai, and the rocket ship took off. In the three years that followed, it built 3 million more. It hit 5 million last September, just five and a half months after reporting 4 million total vehicles. Now 6 million, and … how soon 10 million? 20 million?

The Nissan Leaf, which began deliveries 18 months before the Model S, took 10 years to reach even half a million sales. Nissan said last summer it had surpassed 1 million global EV sales—a milestone that required 12 years. General Motors sold 160,000 thousand Chevrolet Volts in two generations before killing the car (plug-in hybrids are very hard to explain, and there’s no guarantee they’ll ever be plugged in). Meanwhile, its much-vaunted array of Ultium-based EVs is now far behind schedule amid production problems and product glitches.

Tesla may soon lose the EV portion of its title to China’s BYD, however. BYD said just last week that it had sold 7 million cumulative “new energy vehicles”—including plug-in hybrids. In sheer production of vehicles with plugs, BYD has surged ahead of Tesla. It reported sales of more than 3 million plug-in vehicles in 2023 alone, although it remained behind in battery-electric sales, at 1.6 million vs. Tesla’s 1.8 million.

2007 Tesla Roadster Prototype

Tesla followed a traditional innovation path

Historically, almost every major advance in automotive technology has come at the high end of the market—either in luxury vehicles or performance cars. From Charles Kettering’s electric self-starter for combustion engines (Cadillac, 1912) through air conditioning (Packard, 1939) and automatic transmissions (Oldsmobile, 1948), more expensive brands and models pioneer new features because they deliver more profit margin to offset the cost of the new technologies. Things like disc brakes (Jaguar, 1952), fuel injection (Corvette, 1957), and turbocharging (Corvair Monza, 1962) came from the performance end of the scale—but all of these innovations gradually migrated down the lineup as they were made simpler, more reliable, and less expensive.

Tesla followed this path to a T, versus Nissan and Chevrolet, which launched their EVs as compact hatchbacks under $40,000. The first Tesla, really a proof of concept, was the low-volume, high-performance 2008 Roadster, carrying a six-figure price tag. Then came the Model S and Model X in 2012 and 2015, higher volume and somewhat lower-priced. The Model 3 cost under $50,000 when it debuted in 2017, as did the Model Y in 2020. Cybertruck aside, it’s spoken of a cheaper, $25,000 Tesla (often called the “Model 2”) to boost its volume even higher.

2020 Tesla Roadster

What Tesla Hasn’t Done

Tesla CEO Elon Musk says many things. Some are verifiably true when he says them. A few are verifiably false. And many may be true at some point in the future but remain, at best, aspirational on indefinite timelines rather than being actual features or products with defined launch dates.

Tesla hasn’t offered hands-off automated driving

The development history, extravagant marketing claims, and misleading titles of Tesla’s “Autopilot” and “Full Self-Driving” automated driving assist systems are their story, if not book or perhaps multi-volume series. But while both add active lane control to adaptive cruise control, they remain “hands-on” systems in which a driver must keep their hands on the wheel and pay attention to the road ahead. This is noted on Tesla’s website, but not widely appreciated by those who believe it sells “self-driving cars.”

Tesla may get there one day, but it’s not there now, while other makers are. As for the company’s claim that owners would get paid for letting their idle Model 3s act as robotaxis when not needed, we’ll just move right along. It’s several years overdue now … and counting.

2025 Tesla Cybertruck – Courtesy of Tesla, Inc.

Tesla hasn’t proven it can compete in full-size pickup trucks

While North American full-sized pickup trucks are simply too large for much of the rest of the world, they remain the core source of profits for the two and a half surviving Detroit automakers. While the Cybertruck has innovative technology in multiple areas, even if Tesla can overcome the challenges of building a high-quality vehicle with angular stainless-steel body panels, it remains unclear whether truck buyers want a vehicle that looks like a prop from a dystopian movie.

Tesla didn’t eliminate franchised auto dealerships

When Tesla started, franchise laws in most states banned automakers from selling cars to retail buyers if those sales competed with their existing franchised dealerships. Tesla had none of those, so it saw no problems setting up its own Stores to educate shoppers about EVs and assist them in ordering the cars online directly from the factory. State auto-dealer lobbyists saw this as an existential threat, and swiftly got laws changed to ban all direct sales, period.

Tesla Store – Portland OR

Fifteen years later, the result is a patchwork of different state laws on where Tesla can legally sell cars to customers and where it can’t. In Texas, where Tesla has its headquarters and where it built its second vehicle assembly plant, it is technically illegal for Tesla to sell cars to Texans. Workarounds exist, but it shows the enduring political power of auto dealers en masse and their lavish lobbying dollars.

Silicon Valley types often say dealers are unnecessary friction, intermediaries who serve no purpose beyond service and repairs, an anachronism that will inevitably fade away. Dealers have other ideas, and so far—despite their well-documented problems of knowledge, understanding, and ability to sell EVs—the dealers are still standing.

![Tesla Motors battery-swapping station at Harris Ranch, California, Dec 2014 [photo: Teslarati.com] Tesla Motors battery-swapping station at Harris Ranch, California, Dec 2014 [photo: Teslarati.com]](https://images.hgmsites.net/lrg/tesla-motors-battery-swapping-station-at-harris-ranch-california-dec-2014-photo-teslarati-com_100499144_l.jpg)

Tesla Motors battery-swapping station at Harris Ranch, California, Dec 2014 [photo: Teslarati.com]

Tesla hasn’t shown battery swapping makes sense

As of earlier this month, Nio claimed to have opened over 2,300 swapping stations in China and Europe, conducting over 40 million battery swaps to date.

But Tesla’s one foray into battery swapping—previewed with much hoopla in June 2013—never succeeded. The single swap station in Harris Ranch, California, was built by early 2015 but quietly shut down the next year, with Musk claiming customers weren’t interested.

EV advocates suggested it had been largely an effort to gain extra ZEV credits for Tesla under California laws that awarded more credits for faster “fueling,” largely intended to give hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles an advantage. Those laws were later changed.

Elon Musk at Tesla Model 3 reveal

Tesla hasn’t moved beyond Musk

Elon Musk has always been the most public of CEOs, with huge followings on social media and in the news. He runs multiple companies simultaneously (Tesla, SpaceX, Neuralink, The Boring Company, and now X nee Twitter). His pronouncements are treated as gospel by his fans, and his political leanings seem to have become more extreme of late. He has been taken to court by numerous parties, from the Securities and Exchange Commission to a private citizen whom he called a pedophile in a tweet.

The question for Tesla, though, is what would happen to the company and its image for innovation, advanced technology, and general coolness if Musk were unexpectedly out of commission. It’s unclear when or even whether Musk will relinquish the reins—though his workload seems more suited to five separate CEOs—despite his off-hand mention on an investor call that he had internally identified a replacement. Companies the size of Tesla have considerable momentum to carry on with business as usual during executive transitions, but continuing to bank mainly on the Musk factor remains a major business risk, one its Board is surely aware of.