Mercedes eSprinter first drive: here’s the deal – it’s a van, but it’s electric

Mercedes invited us out to drive the new eSprinter, the electric version of Mercedes’ cargo van, and if there’s one thing I want you to understand about it is: it’s a van, but it’s electric.

The eSprinter has already been out for some time in Europe, first unveiled in 2018, but that version was not available in the US. Now, the eSprinter has been refreshed into a “2.0” version for the 2024 model year, with significant improvements over the original. And the biggest improvement for the US market is that this version will be available here, unlike the previous version.

In Europe, the eSprinter will be available in 3 battery configurations (56, 81 and 113kWh) and in short- and long-wheelbase versions, but here in the US we’re only getting access to the long-wheelbase, largest battery version, which will be built in Charleston, South Carolina. This spec has a 170-inch wheelbase and a 113kWh LFP battery, with max payload of 2,624lbs.

Despite the lack of battery and wheelbase options, the US eSprinter does have two powertrain options, with either a 100kW or 150kW motor (with 295 lb.-ft of torque). The former would be more useful for intra-city tasks, whereas the latter is better for routes that might include more hills, or for use cases that will more commonly carry close to the full payload.

This is one of Mercedes’ first steps towards its goal to lead in electric vans, targeting 20% of its business being EV by 2026 and 50% by 2030 (which is nevertheless significantly behind California and the US EPA’s targets, at 68% and 60% respectively). The eSprinter currently shares a platform with the diesel version, but in 2026 Mercedes will have a new “VAN.EA” platform as the basis for all of its future vans.

So is the future looking good for Mercedes’ electric vans? Let’s dig in.

Driving feel

We drove in “comfort” mode, which is Mercedes’ name for the mode that unlocks the full 150kW motor power. Eco and maximum range modes limit power to 100kW or 80kW respectively, though in either mode you can use the kick-down accelerator pedal to overcome that limitation and get the full 150kW. In practice, we found the 150kW motor power merely adequate with our 440lb load. I’m not trying to compare to a performance vehicle here, but it feels like a fully loaded van might feel a little lethargic heading up a hill, even on the “high output” 150kW version. A little more power would have been nice, but then again, it’s a van.

Otherwise, the acceleration and ride were smooth, and handling was good as far as you could expect out of an extremely tall and long van. A big chunk of the vehicle’s weight is situated down low, in the battery under the van’s floor, which helps with stability. We did have a bit of a wobbly moment when exiting a driveway at an angle, which bounced us around more than I would expect. Maybe a heavier load would have mitigated this bounciness, but it was a little troubling.

Seat comfort was acceptable, with the seats having some adjustments, but I couldn’t find a way to tilt the seat forwards or backwards. There are a number of other adjustments available, but not that one. These are not luxury seats, but they were fine to sit in. It’s a van. You get what you expect.

The eSprinter has 5 separate regenerative braking settings, adjustable via paddles on the steering wheel. The van doesn’t save these settings between drives, which I think is a mistake, but at least the paddles make it easy to adjust without having to dig into a touchscreen menu.

The strongest setting is just about strong enough to allow for one-pedal driving, but the van also has a blended brake pedal, which activates regen at first and then the friction brakes as you push the pedal deeper. This can lead to some inconsistent braking feel as the van decides which brakes to apply, but some companies do this with the idea that it’s more familiar to drivers who have previously driven ICE cars.

This familiarity is particularly important in the commercial market, where drivers might swap back and forth between diesel and electric vans. So I won’t hammer too hard on this point, but in general I think blended brakes are subpar and that one-pedal driving with strong off-throttle regen and a brake pedal that only activates friction brakes is the superior solution.

One setting which Mercedes was quite proud of was the “D-auto” setting, which automatically applies regenerative braking in certain circumstances, and otherwise allows the vehicle to coast. If the van sees another moving car in front of it, it will apply regen to slow down as the car ahead slows down (even when traffic-aware cruise control is turned off), and also will apply regen on downhill grades in order to maintain a steady speed.

In practice, I couldn’t find much reason to use this setting. It was too inconsistent in application (it doesn’t work for stationary vehicles, for example, a limitation of radar), seemed to activate later than I’d like when tracking leading vehicles, and the coasting function just seemed like a rather mild benefit. Maybe some drivers will find a use for it – a tired foot and coming down the Grapevine, perhaps – but I think most will likely ignore it.

Range and efficiency

The 113kWh battery is estimated at 273 miles (440km) of range under the WLTP test cycle (or 329 miles on the WLTP city cycle), which tends to be more forgiving than the EPA cycle. When we sat down in a fully (99%) charged eSprinter, the readout said “max 235 mi” – so perhaps that’s closer to what we might expect from an EPA estimate.

Over the course of our drive, we didn’t get quite the same efficiency that Mercedes estimates, though some of the other journalists did. The drive happened in typically mild Southern California weather and little traffic, on mixed roads including some surface street driving and some highway driving (at up to 75mph, which the van is electronically limited to). The van was loaded with 440lbs of “cargo” – so nowhere near the total payload, but not unloaded either.

We drove 73 miles and the van’s guess-o-meter went from 235 to 151 and from 99% to 65%, suggesting a total range of ~215 miles in this driving style and conditions. The car said we got 2.0 miles per kWh, but other journalists got up to 2.4 miles per kWh on the day, and in European outside testing Mercedes managed to clock 2.8 miles per kWh. Mercedes also said that it managed to drive from Las Vegas to Long Beach, a 275-mile trip (albeit mildly downhill), on a single charge. So as usual – your mileage may vary.

Either way, all of these numbers are better than the previous generation of the eSprinter, which is apparently rated at around 1.6 miles per kWh. That’s a pretty huge jump in efficiency from generation to generation. And over 200 miles of range is more than enough for many use cases. Mercedes says the primary use case for this vehicle is likely going to be last mile, local delivery-type tasks, and those sorts of routes are rarely anywhere near that high-mileage.

Charging

Unlike many EVs, the eSprinter can be charged to 100% every night, rather than the oft-recommended 80%. This is due to its lithium iron phosphate (LFP) cathode battery, while most EVs currently have nickel manganese cobalt (NMC) cathodes. LFP has many advantages over NMC, such as long-term durability (allowing a full charge every night), lower cost, and avoidance of conflict minerals like cobalt and to a lesser extent nickel.

LFP also has disadvantages, namely lower energy density and worse charge performance in very cold weather. The energy density problem isn’t much of an issue in a large van, since there’s plenty of room for batteries (Mercedes had a cut-away version of the van where we could see the battery and it looked like there was room to spare), and Mercedes says that its battery heating and cooling system will intelligently distribute heat to where it’s needed, and didn’t seem too worried about cold weather performance. And the eSprinter has a heat pump, which should help with cold weather efficiency as well.

Recharging is done either through AC charging at up to 9.6kW, or through DC fast charging at up to 115kW, which can get you charged from 10-80% in 42 minutes. DC charging happens through a CCS port – though Mercedes has said that NACS adapters are coming soon (but no promises for whether the 280-inch-long eSprinter can fit in a Tesla charging spot).

115kW is kind of a low DC charge rate on such a large battery, but Mercedes said that most of its customers will likely charge on AC overnight (AC chargers are cheaper to install, anyway, and can be installed in homes for drivers who take their vans home with them), with quick DC charging being less necessary for its commercial customers. The DC speed limitation is on the charger, though, not the battery, so we wonder if there could be room for improvement in the future if this van proves popular with the overlanding set, or some other group that might make more use of DC charging.

While we didn’t get to test fast charging or see a full charge curve, the van has a helpful feature on the infotainment system that estimates current maximum charge rate, based on battery state of charge, temperature and so on. When setting out with a full battery, this read 20kW – which was perhaps optimistic. But once we got the van down to 65%, it was already reading 113kW as the peak charge rate, which suggests a pretty late taper. Combined with Mercedes’ 42-minute 10-80% estimate, we think the eSprinter should have a rather broad charge curve, able to maintain peak 115kW charging until pretty high SOCs.

One thing the van won’t have, however, is any sort of vehicle-to-load capacity. We’ve started seeing this on commercial vehicles and small SUVs and trucks (and even triangles) lately, so it would have been nice to have it here, but V2L is still a rather niche application after all. It would be nice for an eventual RV upfit, though.

Tech and practicality

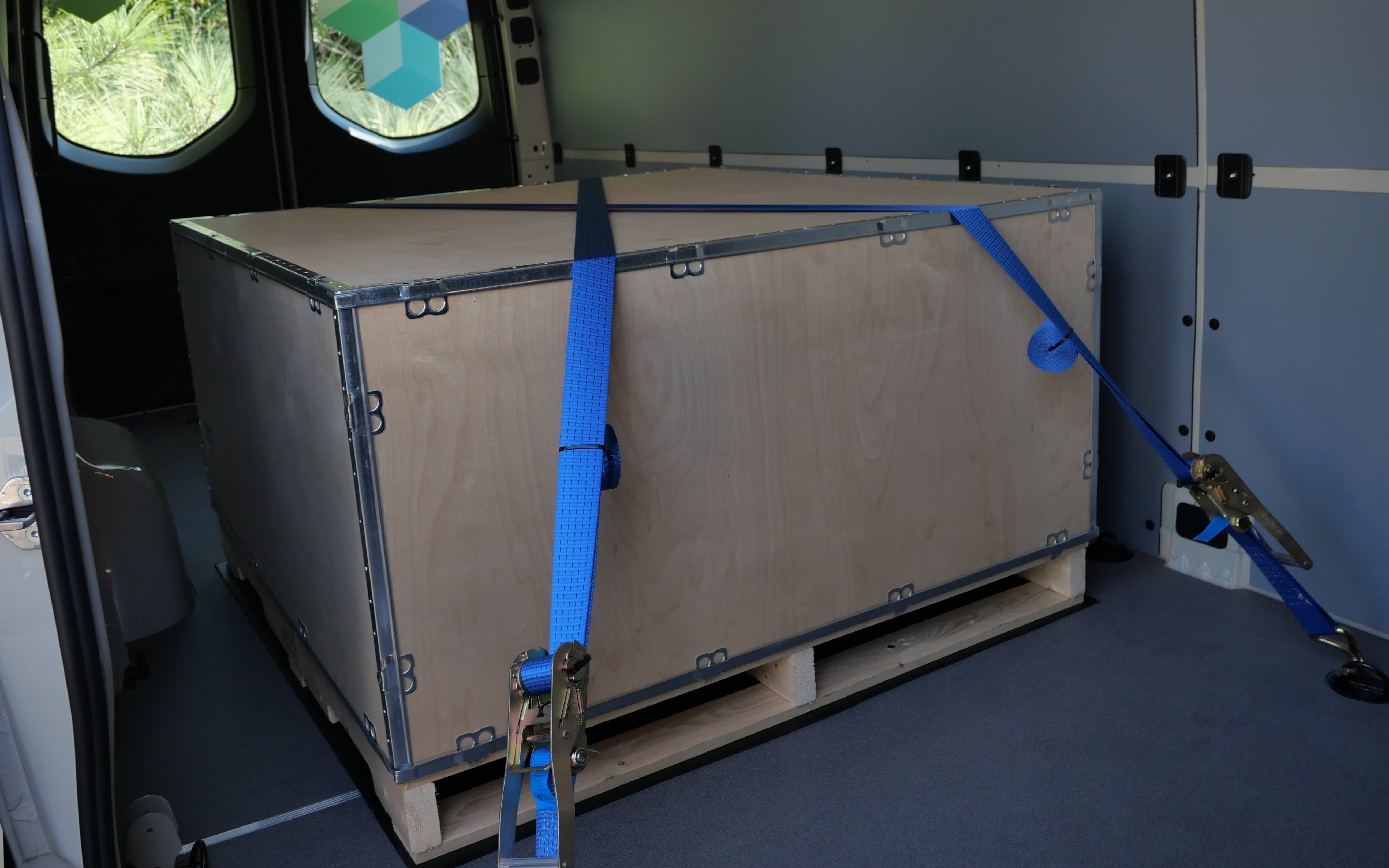

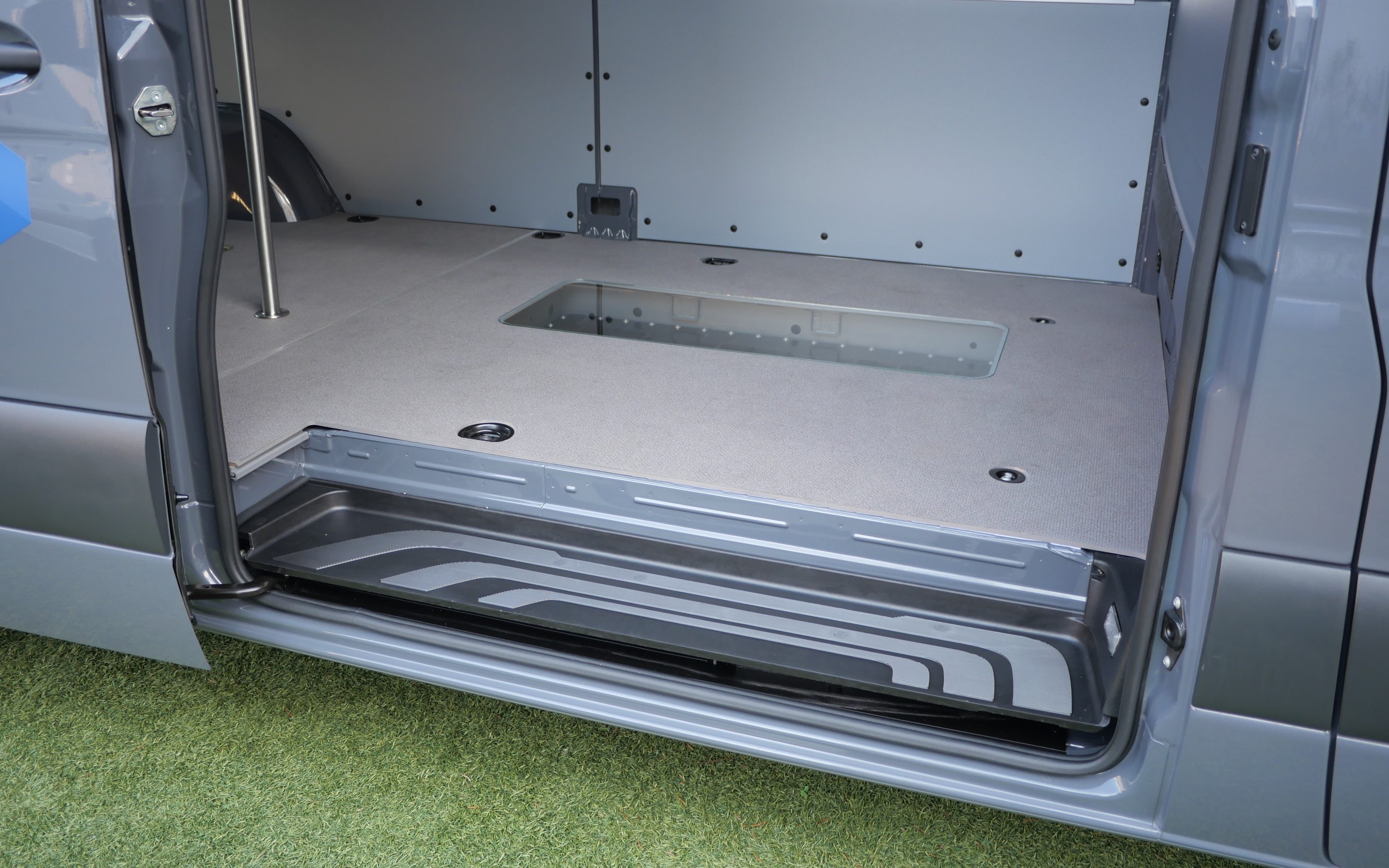

The Mercedes eSprinter has 488.1 cubic feet of cargo volume and a max payload of 2,624lbs. This payload is significantly lower than comparable diesel Sprinters, due to the additional weight of the approximately 1,000lb battery. Towing capacity is also slightly lower, at 4,100lbs compared to the 5,000lb capacity of the comparable diesel Sprinter Cargo Van 2500.

However, no space has been compromised – the floor is the same height as it is in the diesel version of the van, with the battery tucked neatly underneath it, giving the same cargo volume as the long wheelbase, high-roof 2500. This lower payload but significant cargo space means that the van will be more useful for tasks that “cube out” rather than “weigh out” their payloads. So: flower delivery – yes; bulk cinder block delivery – perhaps not.

The van comes with a number of electronic safety aids, like blind spot warnings, attention assist to ensure drivers aren’t nodding off, crosswind assist to help maintain vehicle control at high speeds in crosswinds, traffic-aware cruise control and emergency braking assist.

It also has a digital rear view mirror – on most cars I prefer not to use these, as it forces the eyes to refocus on the mirror itself instead of into the distance, but it’s particularly useful in a windowless van where an optical rear view mirror is simply not an option. The cameras for the rear view mirror are situated high up, under an overhang, and have a heater to reduce fogging, and thus should do well in wet, snowy, or grimy conditions.

The car’s 10-inch touch display runs on Mercedes’ MBUX system, but this is not a giant flashy display as in the EQS, but a rather more practical and informational one – you won’t be watching YouTube videos in traffic here. MBUX and connectivity features can be updated over-the-air, but deeper vehicle functions may require a visit to the dealership.

You can also use wireless CarPlay or Android Auto, and there is a helpful phone tray with 2 USB-C ports and optional wireless charging mat (though the tray is a bit distant to reach for from the seats).

The MBUX UI is pretty good for an automotive infotainment system, and was snappy enough and offered some interesting EV-specific features, like a live preview of anticipated DC charge speed as mentioned above. It does have charge routing, so you can tell the nav system (through “Hey Mercedes” voice functions, which responded… about as well as most automotive voice functions do, i.e., it could be better) to take you somewhere distant and the van will tell you where and how long to stop for charges. This is a feature that Teslas have had for a long time, and other EV brands are finally implementing.

One negative of the UI stood out to me, though. This will seem small to many, but I noticed that the nav system had gas stations turned on as a “point of interest” by default. While this doesn’t really matter and you can turn them off, this is often a worrying sign to me – it means that parts of the UI, and perhaps the underlying vehicle, have been carried over from the diesel version without someone putting thought into what should have been changed. If that’s the case in the UI, where else might it be the case in the vehicle? Are there aspects of the vehicle that could have been optimized better with a clean slate approach, rather than adapting features that are better suited for a diesel vehicle?

I brought this up with Mercedes and they seemed to take this feedback seriously. If nothing else, it’s a little embarrassing to show a vehicle that’s meant to be a part of the future of the brand, and still have a legacy experience built in. Think back to the time early Audi e-trons told owners to get an oil change. So, hopefully that gets rectified (and drivers who still want to see those points of interest can still turn them on in the menus).

Value

The whole package starts at $71,886, or $75,316 for the “high output” 150kW version. Although those prices can change depending on what sort of upfitting solutions each customer seeks, and potentially the availability of government incentives or tax credits.

Mercedes does plan to work with its upfitting partners to create the configurations its customers look for in the Sprinter. We asked specifically if it planned to come out with a first-party vanlife version, but Mercedes says that isn’t in the plans yet for eSprinter, and that it would leave that to third parties. We’ve already seen some electric RVs on other platforms, so we could see the same out of the eSprinter. But later on, with the VAN.EA platform, it sounds like Mercedes might offer first-party electric RVs – but that won’t come until new platform models come out in at least 2026.

In terms of value, the base price of the eSprinter is significantly higher than the diesel version (about $15k), which is offset by much lower fuel costs and presumably less maintenance cost. The eSprinter can also benefit from various government incentives in different regions, potentially bringing upfront cost down significantly (particularly since sometimes business incentives can be higher than consumer ones).

And of course it has the benefit of not choking you, your family, your employees, your customers, and literally every other living being on the planet to death with fossil fuel exhaust which is responsible for literally millions of deaths per year – so that’s a pretty nice bonus.

Conclusion

The long and the short of this whole review is that my experience driving the Mercedes van just felt very normal, and that’s exactly what’s needed for the commercial market. I have my own preferences when it comes to electric cars, but most of the cars I test are vehicles intended for personal ownership, where people can buy cars with features and design that fit their personal tastes.

But for the commercial market, what matters is simplicity, predictability, familiarity. Drivers may drive these vans every day, or may swap between several vans in a fleet, only some of which are electric. And those drivers may or may not be sold on the whole idea of driving electric, unlike the consumer market where buyers generally know they’re in for a somewhat different experience when they decide to buy an EV.

So practicality is of maximum value here, and I think Mercedes has succeeded at that. Nothing really stood out tremendously in my drive of this van, and that’s just how it ought to be.

That said, I have said many times before that rather than making a great car that just happens to be electric, you should make a car that’s better because it’s electric. That contrasts somewhat with my conclusion here – but we’re also dealing with different markets. For a workhorse vehicle like this, I don’t mind a more conservative approach.

I do think that a future van built off of an electric-only platform (coming 2026+) will likely be a better total package. Ground-up EVs tend to be better than shared-platform EVs, and that’s a tendency we’ve observed for a long time.

But my misgivings about the eSprinter are largely quibbles here and there, with nothing particularly glaring. It’s a competent entry that will pencil out for many fleets, and there’s certainly a lot of low-hanging fruit in the commercial market that could electrify quickly right now (and, given California’s new rules, a lot of them need to ASAP). For a fleet that’s looking for an easy and familiar way to clean up its fleet and save some money on fuel – a fleet that’s looking for something that’s, you know, a van, but electric – the eSprinter is a solid choice.

FTC: We use income earning auto affiliate links. More.